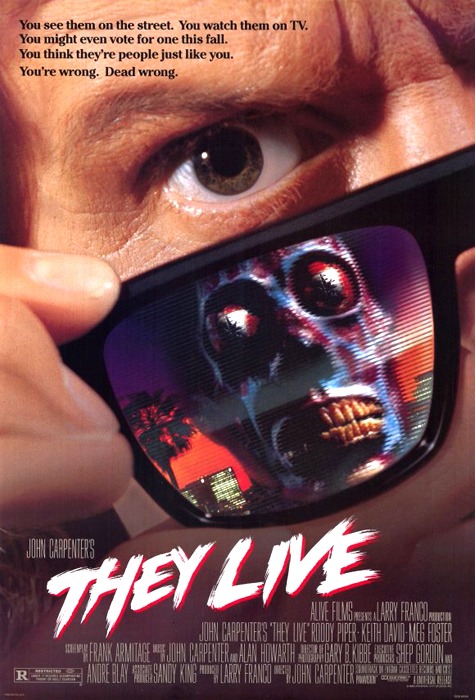

(USA 1988)

“I’ve come here to chew bubblegum and kick ass…and I’m all out of bubblegum.”

“I’m giving you the choice: either put on these glasses or eat that trashcan.”

“Brother, life’s a bitch. And she’s back in heat.”

— Nada

Director John Carpenter has done a few good pictures that probably will have an audience long after he’s gone; They Live isn’t one of them. At least, not in a good way. B-movie cult fodder all the way, They Live is a somewhat delayed and really heavy-handed reaction to ’80s conspicuous consumption. Based on Ray Nelson’s 1963 short story “Eight O’Clock in the Morning” and subsequent comic strip, Carpenter’s screenplay, written under the pseudonym Frank Armitage, is founded on a decent premise; it just doesn’t go where it could have.

Nada (Roddy Piper), a migrant construction worker who’s seen better days, picks up a job in downtown Los Angeles. He notices some weirdness going on with a television station that seems to be connected to a church across the lot where he and other homeless people have set up camp. His coworker Frank (Keith David) doesn’t want to hear about it. No one does.

One morning, Nada comes into possession of a pair of sunglasses. When he puts them on, he sees subliminal messages everywhere. A billboard with the tagline “We’re creating the transparent computing environment” says “Obey” with the glasses on. A travel ad beckoning, “Come to the Caribbean” says “Marry and reproduce.” “Men’s apparel” says “No independent thought.” Signs all around him order one to consume, conform, buy, watch TV, submit, sleep, do not question authority:

Even the dollar bill has a different message: “This is your god.”

What’s worse, some people are not what they appear to be. At all. They aren’t even human — they’re skeletal reptiles, a kind of mutant species of Sleestaks or something:

What the hell is going on? Who are these things? What do they want? As Nada tells Frank, they ain’t from Cleveland.

I remember seeing They Live at the theater when it was new. It was okay. Three decades later, it’s still okay. It’s a lot sillier this time around, though. The whole thing gets off to a good enough start, but the momentum peters out just before midpoint. Carpenter — or anyone, for that matter — can get only so much mileage out of this story. They Live feels like 40 minutes of material stretched into more than twice that amount of time.

The denouement is not just predictable but anticlimactic, and the perspective here is adolescent at best. The lines are cringeworthy, falling painfully short of the Arnold Schwarzenegger zingers they aim to be. The acting is pretty bad, especially David and Meg Foster, both of whom are as stiff and lifeless as a dead gerbil. Surprisingly, Piper and his mullet are the best thing about They Live; Piper isn’t enough to carry it, though. And that wrestling scene in the alley is inane — misplaced, unnecessary, and too long, it adds nothing except maybe ten minutes to the running time.

The worst thing about They Live is that it seems Carpenter was serious — nothing here reads as tongue in cheek to me.

With George “Buck” Flower, Peter Jason, Raymond St. Jacques, Jason Robards III, Lucille Meredith, Norman Alden, Norm Wilson, Thelma Lee, Rezza Shan

Production: Alive Films, Larry Franco Productions

Distribution: Universal Pictures

94 minutes

Rated R

(iTunes rental) D+

http://www.theofficialjohncarpenter.com/they-live/