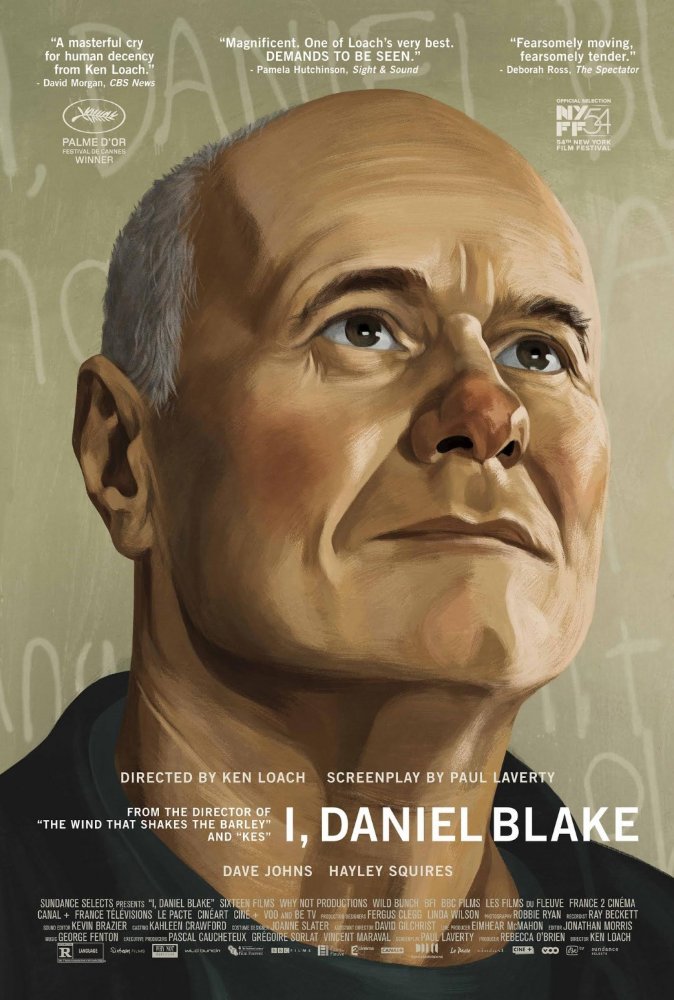

(UK/France/Belgium 2016)

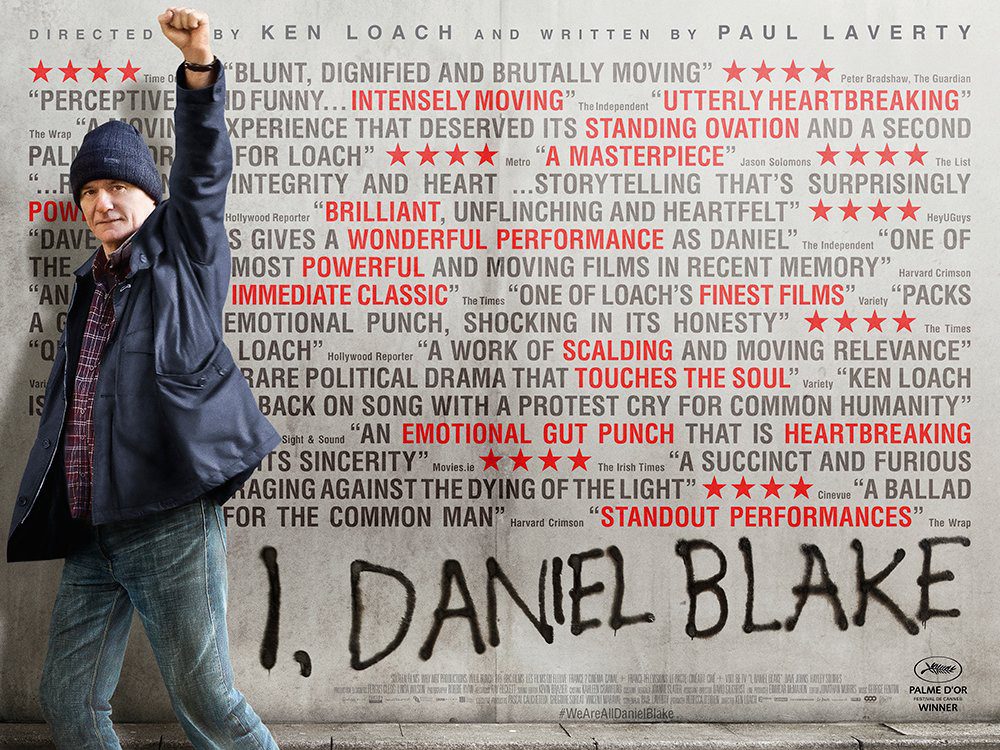

Ken Loach’s I, Daniel Blake has gotten a lot of attention and praise. Good: it wrestles with a topic that’s timely on both sides of the Atlantic—and elsewhere, for that matter. A political and poweful message, Loach has touched many a nerve. Case in point: I, Daniel Blake won the Palm d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, where it finished with a 15-minute standing ovation (http://variety.com/2016/film/global/palme-dor-ken-loach-rebecca-obrien-1201785482/). 15 whole minutes?! Wow.

Daniel Blake (Dave Johns) is a kind of antihero. He’s gruff, he’s private, he’s not handsome or young. He probably goes to church. A heart attack seems like the thing that would change his life, but what really does is a new neighbor (Hayley Squires) and her two kids (Briana Shann and Dylan McKiernan).

I didn’t stand up, but I get it. Bureaucracy versus common sense is always fertile ground for storytelling. I applaud Loach for what he’s saying here, I really do. I, Daniel Blake is a good film: it’s engaging, brave, and relatable. The acting is good all around. So is the premise.

In my opinion, though, it just isn’t a great film. We’re talking shades of meaning here, so if you have five seconds to spare, I’ll tell you why. First, I’ve seen this device many times before—in the last year, even. A cranky old man meets a character that represents youth and hope, and it totally melts the icy facade and changes his life. Well, OK. This sense of hope is usually personified by the very person society looks down on. Next?

Second, I saw where the plot was going way before I got there. Again and again. Predictability is never groundbreaking.

Third, I can’t help but think that this film takes the easy way out. A heart attack in a movie ends only one way. And it’s only a sad ending. Yeah, I, Daniel Blake is emotionally manipulative.

So, my issues center on Paul Laverty’s writing. I wish I had a better way to tell this story. I don’t. For all its pluses and minuses, though, I’d rather watch something more intense. Overall, I, Daniel Blake is disappointingly soft.

With Kate Rutter, Sharon Percy, Kema Sikazwe, Steven Richens, Amanda Payne, Chris Mcglade, Shaun Prendergast, Gavin Webster, Sammy T. Dobson, Mickey Hutton, Colin Coombs, David Murray, Stephen Clegg, Andy Kidd , Dan Li, Jane Birch, Micky McGregor, Neil Stuart Morton

Production: Sixteen Films, Why Not Productions, Wild Bunch, British Film Institute (BFI), BBC Films, Les Films du Fleuve, Canal+, Ciné+

Distribution: Entertainment One Films (UK), Le Pacte (France), Cinéart (Belgium/Netherlands), Cinema (Italy), Feelgood Entertainment (Greece), Prokino Filmverleih (Germany), Scanbox Entertainment (Denmark), Sundance Selects (USA), Transmission Films (Australia), Vertigo Média Kft. (Hungary), Canibal Networks (Mexico), Cine Canibal (Mexico), Imovision (Brazil), Mont Blanc Cinema (Argentina), Longride (Japan)

100 minutes

Rated R

(Music Box) B

https://www.wildbunch.biz/movie/i-daniel-blake/